The monuments left by the Khmer empire offer one of the most striking examples of how art reflects politics and how politics shapes art.

It does so in two ways, first by legitimising of the political authority of the sovereign, and second by reflecting the drive for imperial power through war and peace-making.

The Angkor Thom and Bayan are the places to look for a snapshot of the intimate linkage between art and politics in classical Southeast Asia.

Although a religious monument like much of Angkor’s heritage, Bayan is also a thoroughly secular and political statement of life in the Angkor period. It has gone through different phases of Hindu-Buddhist art.

One signpost is the alternation between Hinduism and Buddhism, as legitimisation strategies of the rulers after periods of rise and decline of the Khmer empire. For example, Jayavarman VII built the monument to reflect his Mahayan Buddhist beliefs as the ruling ideology of Angkor. His embrace of Buddhism in what had been a staunch Hindu ruling class might have been partly due to disillusionment with Hinduism, including Shaivism, in failing to protect the empire from defeat in the hands of the rival Champa. But his successors, who struggled with the burden of empire that Jayavarman built, the greatest in Angkor history, turned to Hinduism as their fortunes declined. Hence Budhist images on the walls of Angkor were defaced and replaced with Hindu deities. These defacements can be seen quite clearly today.

The bas reliefs of Bayon are full of secular depictions of daily life in Angkor, capturing its multicultural makeup, the social life of the inhabitants and the political role of the ruling elite, including the powerful Brahmin clergy.

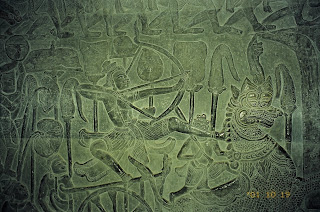

But the most vivid illustrations in Bayon depict battles between Chams and Khmers. It shows the Cham sacking of Angor, as well as the Khmer counter-attack and eventual victory that firmly re-established Angkor’s supremacy over its neighbour.

One interesting facet of the story told in bas reliefs is a scene where a retreating Khmer army if being pursued by Cham soldiers. It would be odd for a ruler to show defeat of his own forces in the hands of foreign invading forces. But this anomaly could be explained by the fact that Jayavarman VII was himself being helped by the Chams to recapture powers by defeating the ruler who had usurped the throne of Angkor.

Angkor Wat is the largest temple complex in the world. Although of less political import than the Bayon complex, it nonethless was a legitimating device for the rulers of Angkor. The bass reliefs of Angkor Wat depict scenes from Ramayana. The design and structure of the Angkor Temple is unlike anything in India. There are significant variations in the appearance of Rishi,Apsaras,Rama and Hanumana. Angkor Wat vividly illustrates the localization of Indian art and design.

BAYON AND ANGKOR THOM

The Faces of Bayon

Scenes of Battle

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Social Scenes

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Elephant Terrace

Punishment Chambers

Phimeanakas

ANGKOR WAT

King Suryavarmana

Rama and Hanumana at War

Hanumana

Brahmana/Rishi

Apsaras

Battle Scenes from Ramayana

Overviews

BANTAY SREI